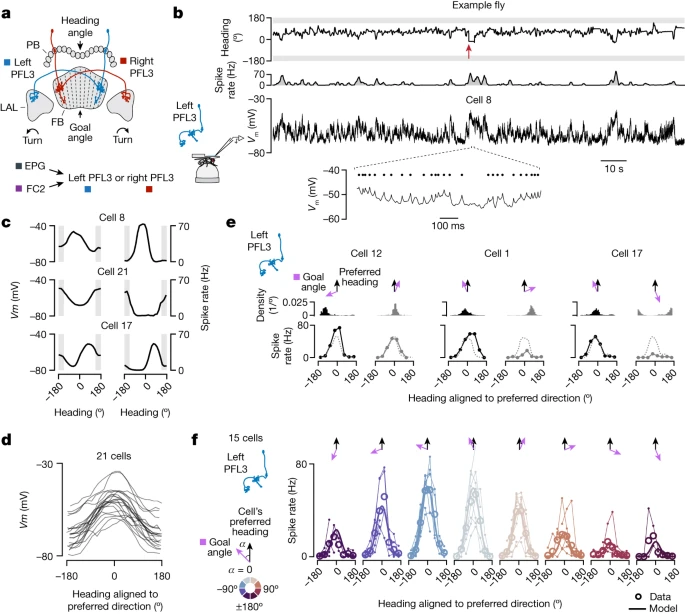

PFL3 neurons show conjunctive spike-rate tuning to heading and goal angles

Decoding Navigation: From World-Centered to Body-Centered Control

Posted on Oct 24, 2024 by Alex Alvarez

In a recent study, *Converting an Allocentric Goal into an Egocentric Steering Signal* (Nature, 2024), Pires et al. reveal how the Drosophila brain navigates through complex environments by converting world-centered (allocentric) information into body-centered (egocentric) control signals. This fascinating exploration into insect neural circuits builds on decades of research into spatial navigation and motor control.

The Central Complex: A Hub for Navigational Signals

The study focuses on the central complex of the fly brain, a region known to process information related to orientation and navigation. Specifically, it looks at three neuron types—EPG, FC2, and PFL3—that work together to convert the fly’s heading and goal angles into steering commands. By comparing the moment-to-moment heading (encoded by EPG neurons) with a fixed goal angle (represented by FC2 neurons), the fly’s brain generates an egocentric output suitable for motor control.

Experimental Insights

"EPG and FC2 neurons connect monosynaptically to a third neuronal class, PFL3 cells. We found that individual PFL3 cells show conjunctive, spike-rate tuning to both the heading angle and the goal angle during goal-directed navigation."

Using advanced imaging techniques, the researchers observed that the EPG and FC2 neurons display stable activity patterns that correlate with the fly’s heading and goal directions. When FC2 neurons were optogenetically stimulated, the flies oriented themselves along experimenter-defined paths, validating the hypothesis that FC2 activity reflects goal angle encoding. These insights pave the way for understanding how neural circuits translate allocentric signals into egocentric outputs.

The Role of PFL3 Neurons

The PFL3 neurons act as integrators, comparing the inputs from EPG and FC2 neurons. They produce a steering signal that directs the fly to adjust its movement until its heading aligns with its goal. This model of navigation shows how a fly’s brain balances these signals to maintain orientation, even when external disturbances occur. The study suggests that these neurons compute the difference between the allocentric heading and goal angles to create an egocentric command that can be used by the motor system.

Conclusion

The study by Pires and colleagues provides a comprehensive look at how navigation circuits transform spatial information in the fly brain. By understanding these mechanisms, we not only learn more about insect behavior but also gain insights into the fundamental principles of spatial navigation that could apply across species, including humans. As we unravel these circuits, we inch closer to replicating such sophisticated navigation in artificial systems.